| As I developed my understanding of the cycles, I was working

on several tracks at once. I was looking for precise details

about the course of fashion, art, and other areas of culture. I was refining my sense

of which factors were unique to particular cycles and which were recurrent. And I was putting a theoretical

framework in place that could give my conclusions more structure and

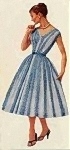

rigor. Charles Fort famously said, "One measures a circle, beginning anywhere," and that is eminently true of the cycles. However, the simplest and most accessible place to start is probably with fashion -- and specifically with the point of transition from organic to geometrical styles. Not only is this transition typically abrupt and dramatic, but its course is strikingly similar from one cycle to another. Much the same processes are always at work as designers modify old fashion devices, and occasionally invent new ones, to bring the silhouette into conformity with an ideal geometrical form. ***** Let us begin by looking at examples from the last few years of three successive organic periods. During this concluding stage, the fashion silhouette is still based on the natural curves of the female body, but in has become exaggerated to the point where the actual lines of the body are almost entirely concealed. The typical outline is that of a figure-8, with the upper and lower torso being not only greatly inflated but also separatedf from one another by a very narrow and sharply indicated waistline.     The first example shows three outfits from 1833. In the first half of the 1830's, women's sleeves became more and more extreme -- often being held out by wires or bags of down -- until they grew larger than the torso itself and eventually merged into a kind of horizontal shelf which stretched from elbow to elbow and beyond on either side. Hats were also large and rounded, while skirts had a bell shape that magnified the line of the hips. The second example shows two women dressed in the height of fashion from 1901. This time it is not the sleeves but the torso itself which has become inflated like a balloon, reinforced with stays to hold its shape, and further exaggerated by the so-called S-bend corset, which forced the upper body forward and the hips back. Skirts not only curve out over the hips but then narrow towards the knees before swelling out a second time around the hem, and hats again are large. The final two examples are from 1957. By then, women's clothing had become far simpler and less extravagant than 50 or 100 years earlier, but we can still recognize the familiar figure-8 silhouette, with the upper and lower halves of the body separated by a tightly nipped-in waist. The upper torso is widest not at the bust but across the shoulders, curving upward and outward in a kind of tulip shape, and the skirt mirrors it almost as if in a mirror -- either extending widely over crinolines as in the 1830's or curving out around the hips and then in again as in the early 1900's. ***** If I had merely picked out three random examples of figure-8 styles from different eras, the similarities among them would be of no particular interest. What makes the commonalities significant is that each of these styles came at the very end of a period of organic fashion, represented a final exaggerated statement of the norms of that period, and was immediately succeeded by a rapid transition to the pyramidal or rectangular styles typical of the succeeding period of geometrical fashion. The first phase of geometrical styles always begins with a rapid succession of fashion mutations, as designers modify, tweak, and reconfigure existing elements to fit them into a simple, linear form, almost like programmers debugging a piece of software. For example, the images below show the progression from 1837, when women suddenly decided to stop going about with pillows on their elbows, to 1844, when the pyramidal lines that would typify the next 20 years fell into place. In the first image, the hyper-inflation of just a few years earlier has been eliminated, but the bell-shaped skirt, the horizontal detailing across the bust, and the upward twirls of hair all remain, producing at most a somewhat melted-down version of the figure-8.    By the time of the second image, which is from 1839, the fashion designers have clearly been experimenting with devices to fit the overall silhouette into the outline of an inverted V -- and in the third image, from 1844, those devices have been further perfected and the proportions refined. The hairdo grows smaller and smoother and the flared brim of the bonnet retracts. Dresses become extremely tight around the upper arms and shoulders, narrowing that part of the body in contrast with the skirt. The skirt itself is less bell-shaped than before and often has ruffles near the hem, which cause it to to spread out in a more nearly straight line. A loose mantle may also be added to help create the desired linear effect. ***** In the early 1900's, the process was very similar, starting with an abrupt deflation followed by active experimentation that resulted in a highly geometrical silhouette. The initial reduction of the extreme pouter pigeon effect probably began in 1905, and by 1906, the date of the first image below, it was well established. The bosom has become smaller and less overhanging, the hips a bit narrower and less rounded, and the waistline has taken on a smoothly curved hourglass shape instead of serving to split the body into two discrete halves. In the second image, which is from 1908, this smoothing-out has gone still further and the general posture is becoming more upright, especially in the outfit on the right.     At that point, however, a wild card entered the picture. In 1908, the brilliant and eccentric young designer, Paul Poiret, influenced by Japanese and Middle Eastern styles as well as by the emerging modernist esthetic, introduced a radically new silhouette and use of vibrant color, as shown in the third image. Although his innovations were at first more widely mocked than adopted, except by actresses and other bohemian types, mainstream fashion slowly began to move in his direction. By the time of the fourth image, from 1912, the hats and bosoms remain somewhat oversized, but the waist is barely indicated, the skirt is straight and tight, the posture is upright, and the general effect is almost perfectly rectangular. ***** That brings us to the changes of 1957 to 1962 -- which followed very much the same pattern as before. This time the most radical change came at the very start of the transition, in 1957, when French designers dropped a fashion bombshell by introducing a wide range of waistless dresses under a variety of names. However, as the first photo below, from 1958, suggests, these initial attempts were generally ugly, unflattering, and even bizarre, and they aroused more derision than anything else. It was not until Jackie Kennedy popularized the Italian knit suit -- as shown in the second photo, from 1960 -- that a more acceptable variant became generally available. Even then, the new European fashions were slow to catch on, and my own experience as a junior high and high school student in those years bore a much closer resemblence to the gradual changes of 1837-44 or 1906-12 than to the fashion revolutions coming out of Paris and Milan.       Thus my classmates and I continued to wear our old dresses through 1958-59, and the most obvious change in our wardrobes was that we happily ditched our multiple layers of crinolines and let our full skirts hange more loosely -- and, we felt, more becomingly. It was only around 1960 that the actual cut of our dresses changed, with the nipped-in waist giving way to a gently curved midriff. The third and fourth photos above show me as a ninth grader in the spring and summer of 1960, wearing dresses of the new style. In the first of those, the midriff has been emphasized and the waist downplayed by a kind of criss-crossed ribbon effect. In the second, the line of the dress is broken just under the bust and again at the hips -- but the actual waist is not marked at all. (In that same photo, my mother is still wearing a dress of the older figure-8 style, which she had bought a few years earier, with a full skirt, a tulip-shaped halter top, and a pattern of wide floral bands to emphasize its strong horizontal lines.) Finally, in the fall of 1962, I got my very own Italian knit suit to help me look older and more sophisticated for college interviews -- but it proved stiff and itchy and I barely wore it afterwards. The final photo above shows that I did pull it out for my birthday in early 1963, but by the time I got to college the next fall, I was ready for something more relaxed. No doubt the women who had to cope with the ultra-tight hobble skirts of 1912, or the increasingly cumbersome horsehair crinolines of the 1840's, felt much the same way. 12/30/08 |

Background courtesy of Eos Development |